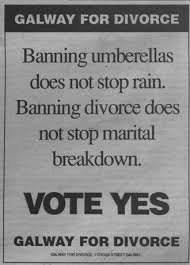

Divorce Irish Style. Part Two

Campaigning against the Divorce Referendum in front of the GPO.

DIVORCE VOTE WAS A SETBACK FOR THE CATHOLIC CHURCH

It’s been thirty years to the week since voters in Ireland narrowly approved a referendum legalizing divorce. The Catholic Church and opponents of divorce predicted that divorce rates would soar, and that once legal, divorce would become all too common.

As it turns out, the institution of marriage is pretty stable in Ireland. Today among the European nations, only Malta has a lower divorce rate. Malta, also an island nation, has the highest percentage of Catholic citizens in Europe. Ireland’s divorce rate is lower than that of the other majority Catholic European nations.

In 1986, Irish voters rejected the legalization of divorce. At the time, nearly 9 out of 10 people in Ireland went to Mass every week. By 1995, when voters took another swing at legalized divorce, only 2 out of 3 were in the pews each week. But that decline in attendance alone doesn’t explain the Yes vote victory on the second try.

The early eighties were horrible years for the Catholic church in Ireland. It never recovered from the revelations about Bishop Eammon Casey of Galway having a wife and son in New York. Then came the drip, drip, drip of the clerical sexual abuse scandal. By 1995 the political clout of the Catholic Church in Ireland was diminished.

Today, hardly anyone attends Mass regularly in Ireland. All those empty church buildings and abandoned pews are that way because only one in three Catholics still attends Mass weekly.

FEAR OF THE UNKNOWN

Before divorce became legal by a vote of the people of Ireland, married women had a tough time establishing any kind of financial independence and claiming a share of the couple’s assets. The same Constitution that forbade the "dissolution of marriage” declared, “that mothers shall not be obliged by economic necessity to engage in labour to the neglect of duties in the home.” In other words, mothers shouldn't need to hold jobs outiside the home. Family law before 1995 deprived her of a share of the family assets should she try to leave her husband.

The No campaign for the divorce referendum in 1986 emphasized uncertainty. Women were told if their husbands decided to divorce them and take up with another woman, they could kiss the house and farm goodbye. The 1995 referendum and some legislation in the early 1990s remedied that by allowing the courts to determine who gets what.

In the aftermath of the massive change in marriage law approved in 1995, the deluge of divorce cases before the courts predicted by the Vote No forces didn’t materialize. There are plenty of statistics about the number of break ups adjudicated, but few stories. That’s because divorce cases were kept confidential by the courts. In fact, the very first legal divorce in Ireland was granted to a dying man who wanted to marry his partner. HIs wife had refused to go along with his desire to divorce until the very end. No names or details of the case were ever released, as far as records show.

COUNTRY VOTERS AND CITY VOTERS

Divorce would not have been legalized in Ireland 30 years ago if it was up to voters in the towns and villages of Ireland rather than the cities. In the Dublin and Cork areas, the Yes vote won handily. In the rest of the country (even in Galway), the majority rejected divorce.

The vote on Nov. 24, 1995, was incredibly close. When all the ballots were tabulated, 50.28% voted Yes while 49.72% voted No. The margin of victory was 9,144 votes. One more No vote in every ballot box could have changed the outcome. While the weather in the West of Ireland was nasty on election day and thus a factor in the turn out, the conditions in the East of Ireland (Dublin mainly) were relatively mild. Better weather in the West might have meant a higher turnout among No voters. Enough to alter the outcome and maintain the Constitutional ban on divorce in Ireland? We’ll never know.

The government of Ireland totally put its thumb on the scale to pass the referendum, spending the equivalent of on a Yes campaign. Just days before the election, the highest court in the land ordered a halt to such spending. After the election, divorce opponents went to court to challenge the result based on that expenditure. The court case delayed but didn’t change the final outcome. On February 27, 1997 divorce in Ireland became a reality.

Poll workers in Dublin sort the ballots on May 24, 2019.

DIVORCE REVISITED IN 2019

Nothing ages faster than the claims made during an election campaign. Voting Yes on a certain candidate or issue will mean the end of civilization as we know it. Voting No will condemn society to living in a political past deprived of any social progress.

Twenty four years after the November 1995 divorce election, Irish voters returned to the polls. The question was whether the four-year waiting period before a divorce could be granted should be changed to just two years. By then, voters had apparently gotten past their fears about the worst-case scenarios for Irish society should divorce become legal. In 1995 the Yes vote was under 51%. Less than 24 years later, on May 24, 2019, the Yes vote was 82%. The vote to approve shorter waiting periods passed overwhelmingly in every precinct in Ireland, even in those where the vote on the 1995 referendum was overwhelmingly No. Ireland, it seems, had come to terms with the modern way of marriage.