The monsignor forgotten by history

Have you heard the one about the Irish priest who saved 6,500 people from the Nazis when they occupied Rome in 1943?

Probably not.

Monsignor Hugh O’Flaherty was born in Co. Cork and educated in Co. Kerry. He was on the Papal staff when Vatican City became a sanctuary city as the Nazis took over Rome. His story has been told in newspapers, books, podcasts and even with a made for TV movie. There’s a statue of him in Killarney, where he grew up. But, as the man who wrote one of those books put it, “The name of this great and good man is largely forgotten in his native Ireland.," (not to mention America).

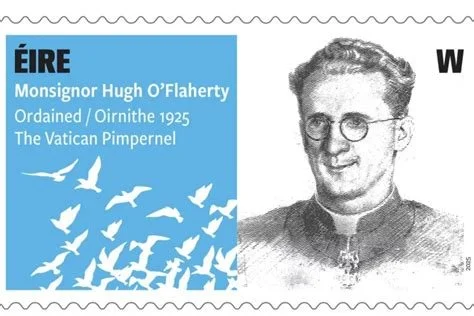

The postal service of Ireland – An Post – recently released a stamp to honor the centennial of his ordination on Dec. 20, 1925. No offense, but loads of people get An Post stamps issued in their names. He was given a Medal of Freedom with Silver Palm by the US government after World War Two. So were 20,000 others. He was named a Commander of the British Empire by England. There are too many of those to count.

Never questioned is the number of Jews, POWs, and Italian resistance fighters Monsignor O’Flaherty rescued from the Nazis. 6,500. When the Allies eventually liberated Rome and the Nazis scattered, the Escape Line (think Undergrond Railroad) he created was hiding 3,925 people, including 1,695 British POWs who had escaped from Italian prisons. As well as 185 American POWs. Some have written that he saved more Allied lives than anyone else during World War Two.

The story of how the good Monsignor managed to save all those souls, though duly chronicled, never caught on with the public the way Oskar Schindler’s heroics did. The movie made about him in 1983 – The Scarlet and the Black – isn’t great cinema. The book with the same name as the movie was based on the one interview Mon. O’Flaherty ever granted. It’s out of print. He never wrote a memoir. Fortunately, author Joseph O’Connor makes the story accessible in a novel he published two years ago, My Father’s House.

"IN MY FATHER'S HOUSE THERE ARE MANY ROOMS."

“He did one interview about this in the course of his whole life, and died in October of 1963. I was born in September of 1963. And I’m very, very glad that for one month, I was on the same planet with the great Hugh O’Flaherty.” Joseph O'Connor

“I was struck by a couple of references in Hugh’s letters to liking American movies. I think he was a kind of George Raft sort of a guy. I think he was an old-fashioned, stand-up guy, that you would have liked to have on your side in a bar fight, as well as a very scholarly man with a love of theology and a love of God. I think he saw himself as the strong, silent type.” (Note. I think he looks more like the Karl Malden type in On The Waterfront.)

If you’re interested in learning more about Mon. O’Flaherty, there’s a podcast. Host Fin Dwyer asked why the man and his story aren’t a bigger deal in Ireland. O’Connor offered three reasons. One. “I think it was partly his modesty.” Two. “What he did was done in the shadows. He didn’t like to talk about it.” Three. “I just wonder if even into the 1960s, if you were still living in rural County Kerry if there might still be a bit of disquiet about someone who had saved all those British soldiers and who had sided with the enemy and so on.”

Monsignor O’Flaherty, born in 1898, was raised on a golf course in Killarney where his father was the greenskeeper. Four of his teen aged classmates were killed by the Black and Tans in the Irish War of Independence. He was outspoken in his anti-British sentiments. Until he got to Vatican City and worked with British officials in Italy to save 6,500 Jews, refugees and POWs from the Nazis.

His mantra was, “God has no country.”