They used to call it “De Valera’s Ireland”

Fifty years ago this past week they buried Eamon de Valera at Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin. Though he obviously meant something to my grandparents, I was only vaguely aware of who he was and why his picture was hanging in their dining room. Kind of an Irish FDR, I imagined in my adolescence. His legacy is a compicated one. Did he do more harm than good to Ireland? Here are some photos with captions capturing just a few elements of that legacy.

This portrait of Eamon de Valera comes from my father’s parents, who emigrated from the West of Ireland 20 years before de Valera came to power in 1932. Willie and Julia Gallagher were supporters in exile. When De Valera toured America during the Irish War of Independence in 1919, they might have gone to see him in person in San Francisco. In Boston, Fenway Park was filled to capacity with supporters. "De Valera divided opinion: some people revered him, others reviled him... in the 50 years since his death the negativity directed at him has greatly intensified."

My four grandparents arrived in America about the time that De Valera was becoming active in Irish affairs by joining the Gaelic League to defend the indigenous Irish language and culture against efforts to make the Irish more English. (He would later marry his Irish language teacher Sinead Flanagan.) The Gaelic League was where many of the leaders of the 1916 Rising first met.

This newspaper photo of de Valera was taken when he was captured by the British during the Rising of 1916. He was commandant of the 3rd Battalion of the Irish Volunteers. After his capture, he was sentenced to death. But at the last minute he wasn't executed because he had been born in America. Actually, there are two versions of why he was spared. He once said it was because he was an American citizen; another time saying that he was allowed to live because the executions of other leaders of The Rising had generated too much negative publicity worldwide for Great Britain. Questions about his paternity endure.

After his escape from a British prison with the aid of Michael Collins and his crew, he headed to America to raise money for the Irish War of Independence that began in Jan. 1919. For most of the War back home he was traveling to U.S. towns and cities wherever Irish emigrants had settled. Thousands of Irish Americans in Portland showed up for his speeches. When in Wisconsin, de Valera was made a Chief of the Chippewa Nation, an honor he later said meant more to him than all the freedoms of all the cities he was ever given. He also spoke to scores of successful Irish American business leaders in order to enlist “wealthy men of the (Irish) race in the industrial development of Ireland’.”

De Valera made the cover of Time magazine as the newly-elected President of Ireland in April 1932. This was just ten years after he fought on the losing side in a devastating civil war in Ireland. His rise to power is considered one of the great political comebacks of the 20th century, But was it his popularity and that of his programs of social spending, or the dire economic circumstances of the Depression, that paved his way to the presidency? Whichever, once elected, he pretty much stayed in power by creating the political party Fianna Fáil (Warriors of Destiny). De Valera was head of the Irish government from March 1932, until February 1948. Later, in the 1950s, he served two more times as Taoiseach (Prime Minister) before he was elected President of Ireland in 1959. Is there any question why Tim Pat Coogan called his biography of de Valera The Man Who Was Ireland?

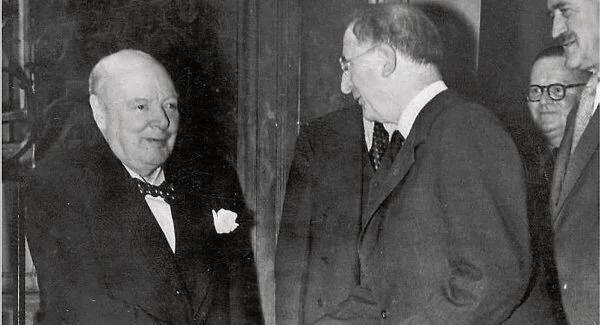

The Government of Ireland decided to remain neutral in World War Two. De Valera didn’t make the call on his own but was the main architect of the policy. This put him at odds with an old adversary from the War of Independence, Winston Churchill. Throughout WW 2 ("The emergency" it was called in Ireland) Churchill was frustrated and angry with Ireland’s leader. Keeping Ireland out of the war may have angered the Allies and Irish Americans whose sons were fighting, but it was popular with the Irish public. And besides, as we learned afterwards, Ireland may have been “neutral”, but was definitely leaning towards the Allies, "The Irish coast watching service reported simultaneously to Dublin and the British. In addition, British aircraft were secretly authorised to fly over Donegal, and the British Navy was allowed to station armed tugs at Killybegs, Cobh, and Berehaven for air-sea rescue purposes.” German troops caught in Ireland were locked up. Captured Allied fighters were sent back to their bases. One of de Valera’s most infamous acts was signing Hitler’s death book at the German Embassy in Dublin.

The caption to this newspaper photo reads, “Old narrowness shoulder-to-shoulder with new horizons: Dev and JFK side-by-side in the summer of 1963.” Here’s how Coogan saw it, “Kennedy’s visit sent a glow through Irish society. For Ireland and the Irish it was as though not one family, but the whole country, had made good. Compared to Kennedy, de Valera seemed a fading, olive-complexioned old man.”

In 1996, the Neil Jordan film Michael Collins put Dev back in the spotlight. His feud with Collins was news. The two of them, once buddies, split over the way the War of Independence ended. Partition - Ireland divided with six counties still under British rule - was unacceptable to Dev and his supporters. Collins argued it was the best they could get or England would unleash an early version of shock and awe. Dev’s side lost the Civil War that resulted. But Dev won the battle over who would shape Ireland for the rest of the century.

RTE - On 2 September 1975, Éamon de Valera made his last journey through the streets of Dublin to his final resting place at Glasnevin Cemetery. De Valera’s remains were taken from St Patrick’s Hall in Dublin Castle to the Pro-Cathedral, where a requiem mass was celebrated by his grandson Father Seán Ó Cuív, and then on to Glasnevin cemetery.

On a day of national mourning, over 200,000 people paid tribute to the statesman along the three mile funeral route from Dublin city centre to Glasnevin. The Army No. 1 Band played ‘Wrap the Green Flag Round Me’ as de Valera was carried into Glasnevin Cemetery.

TO BE CONTINUED